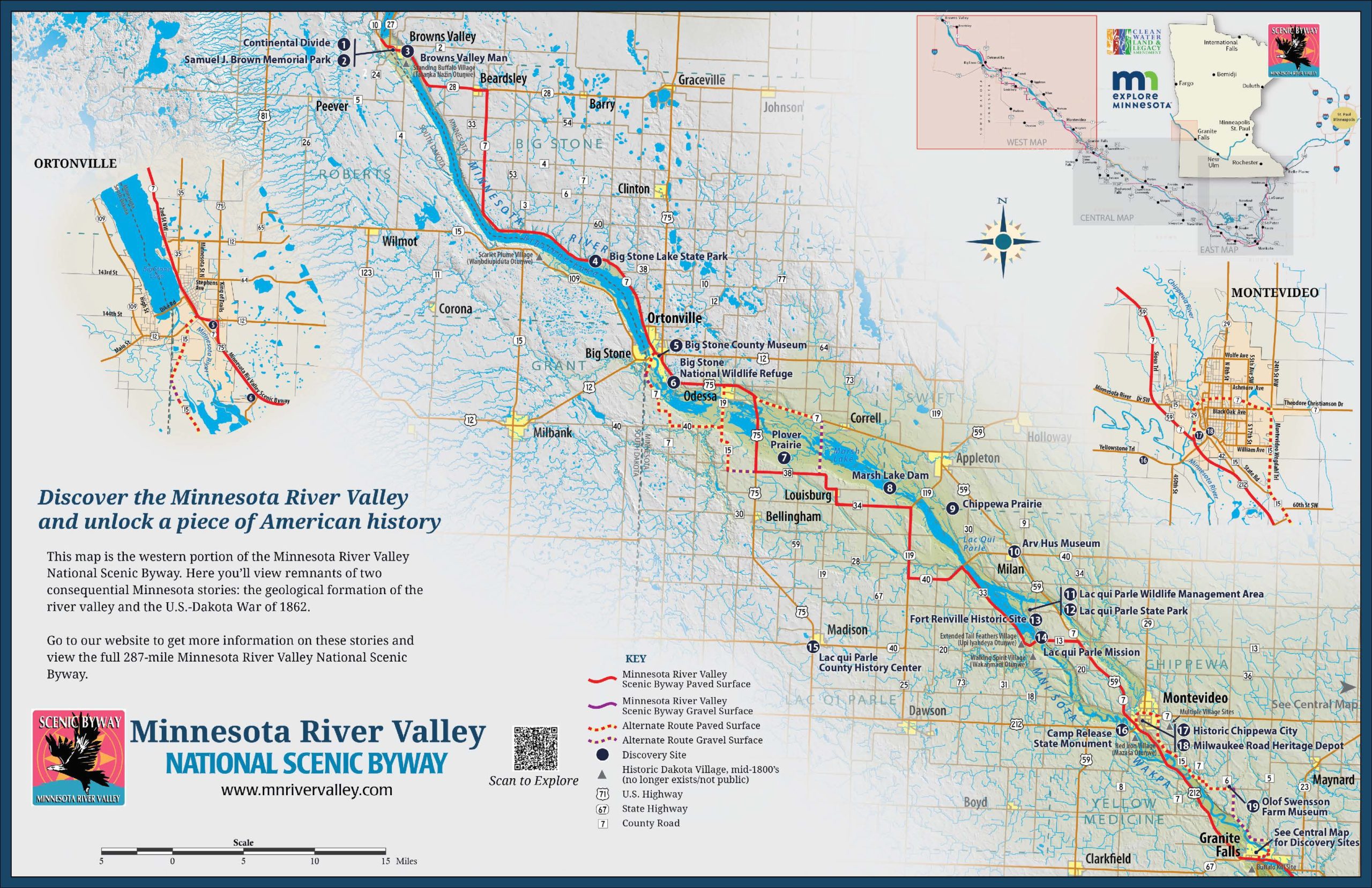

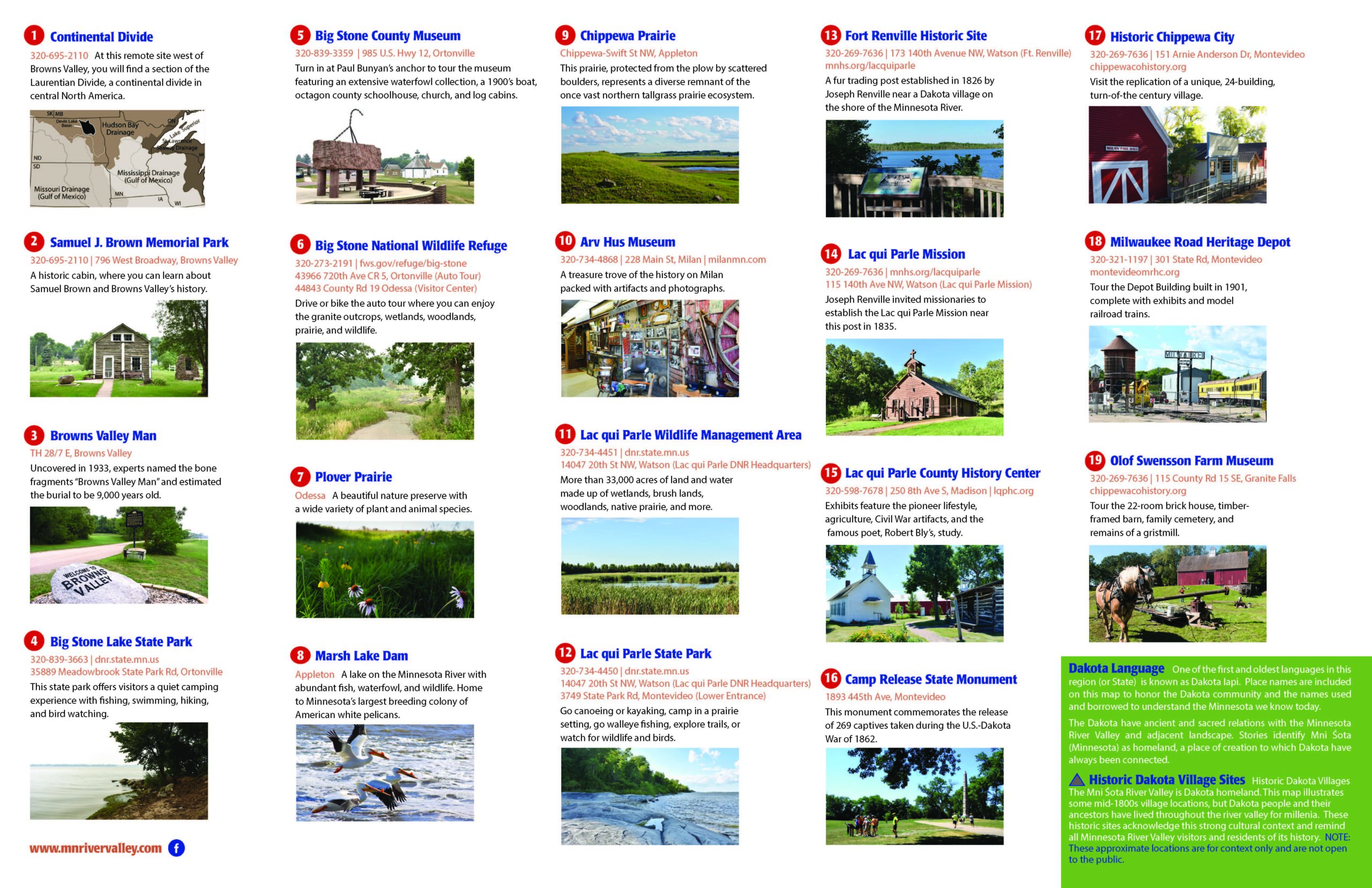

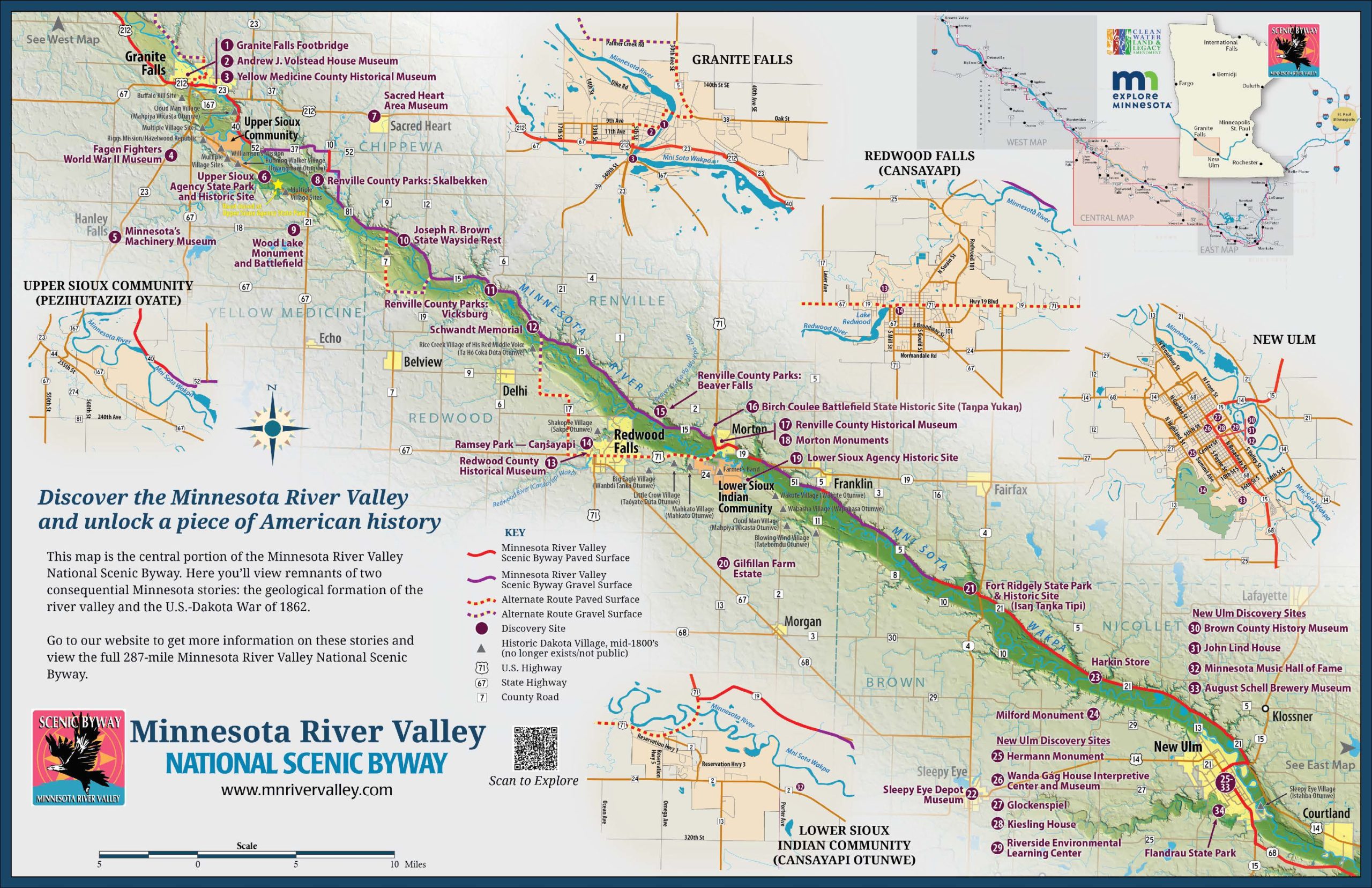

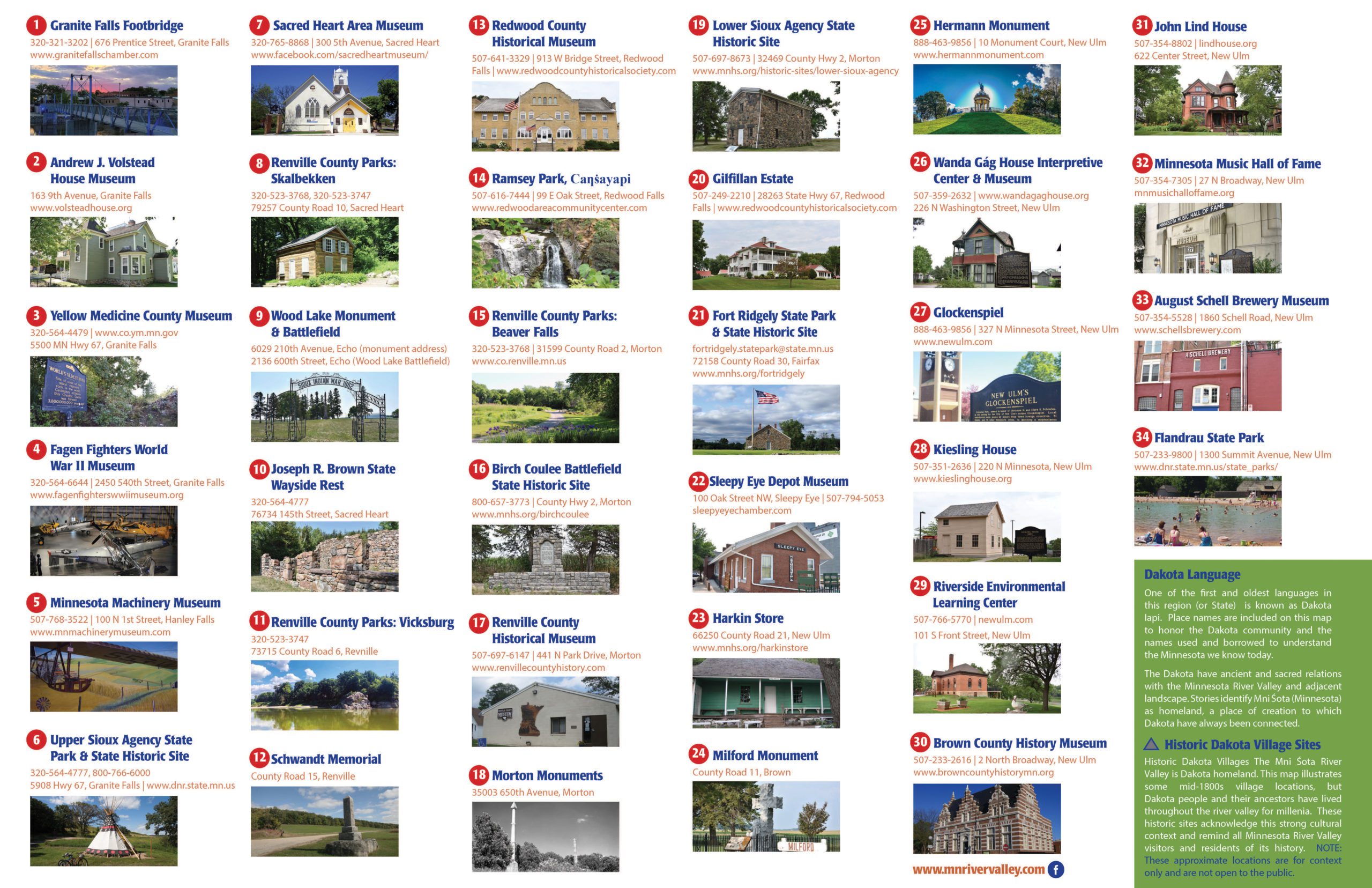

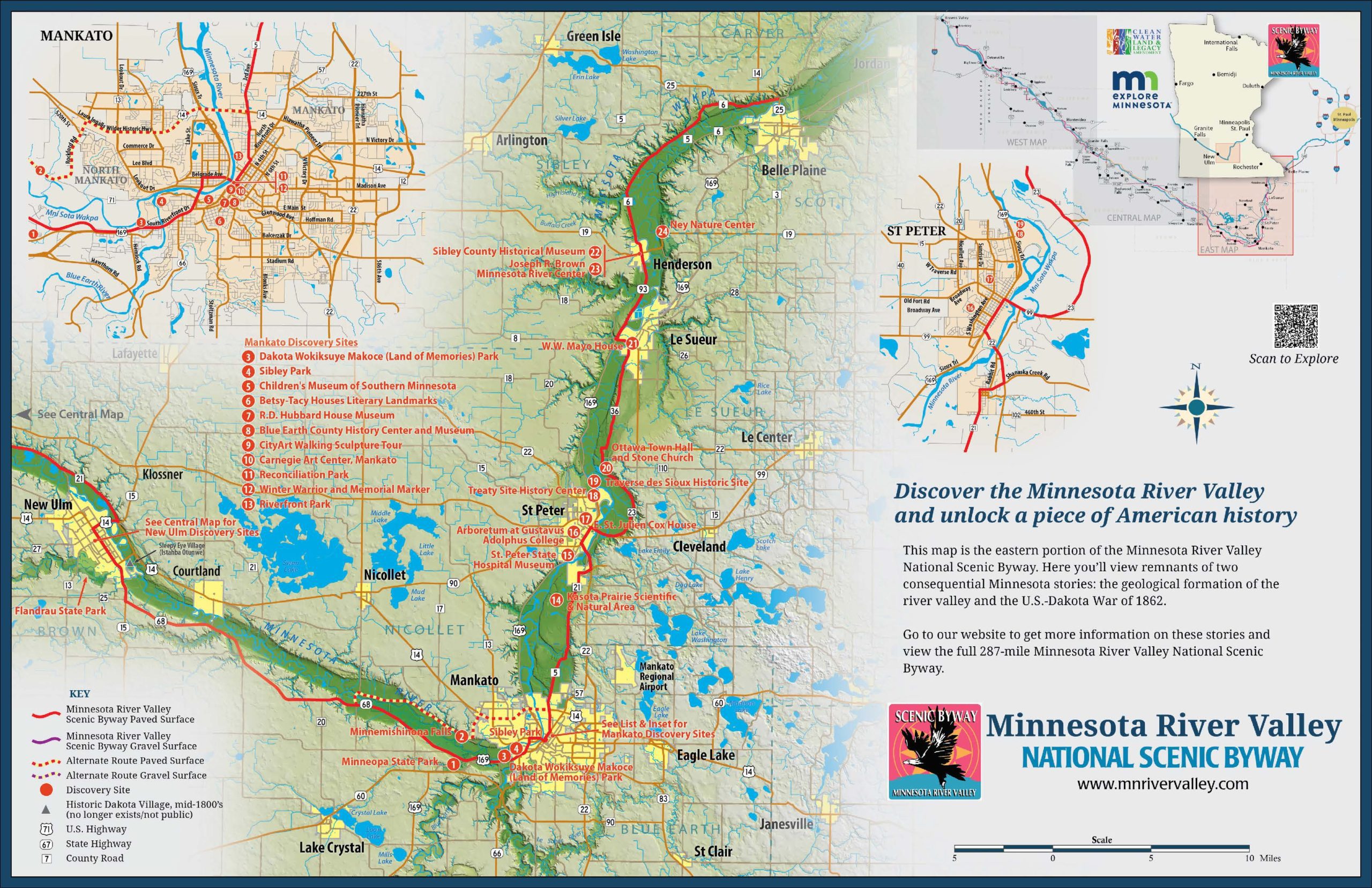

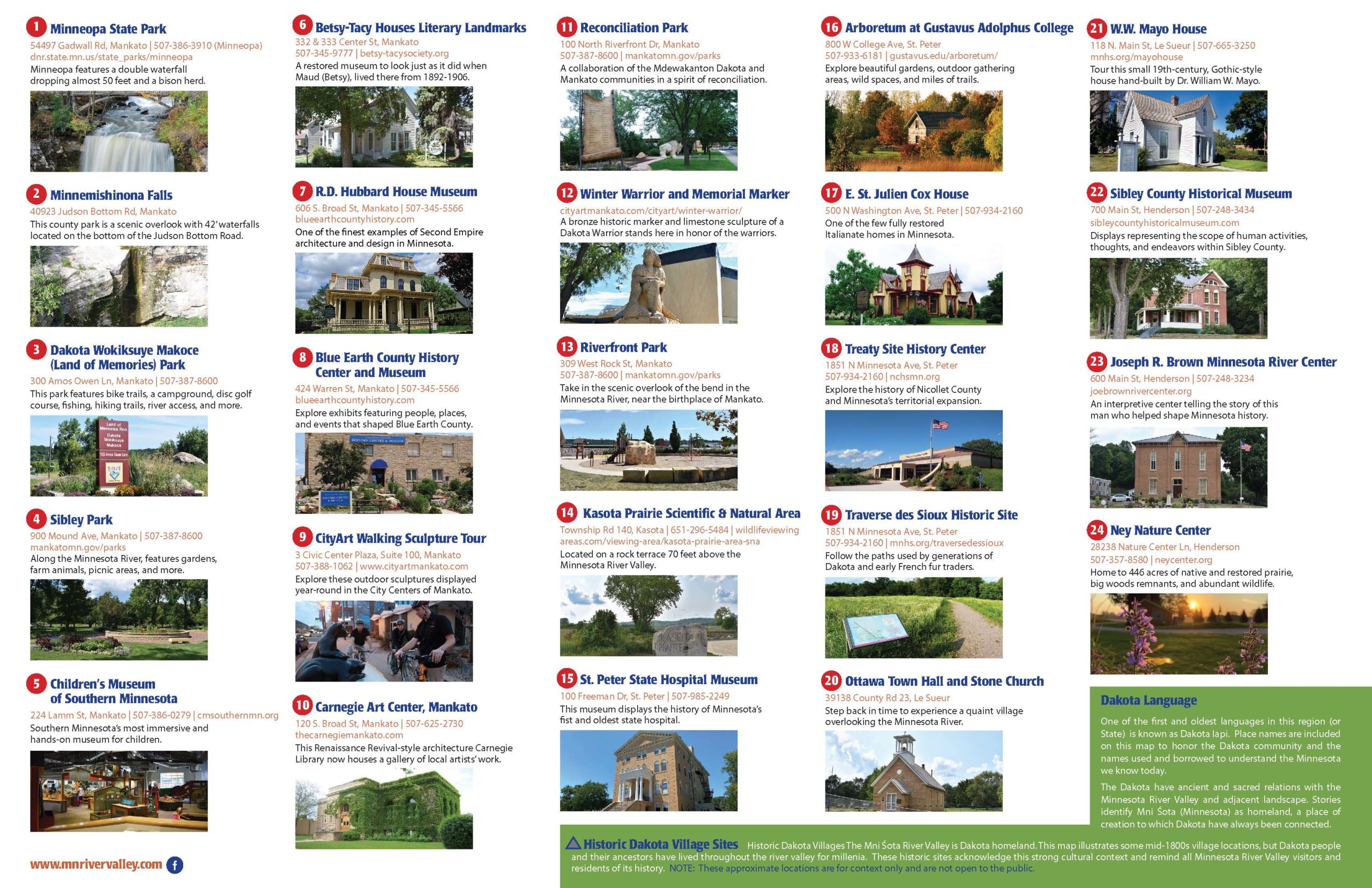

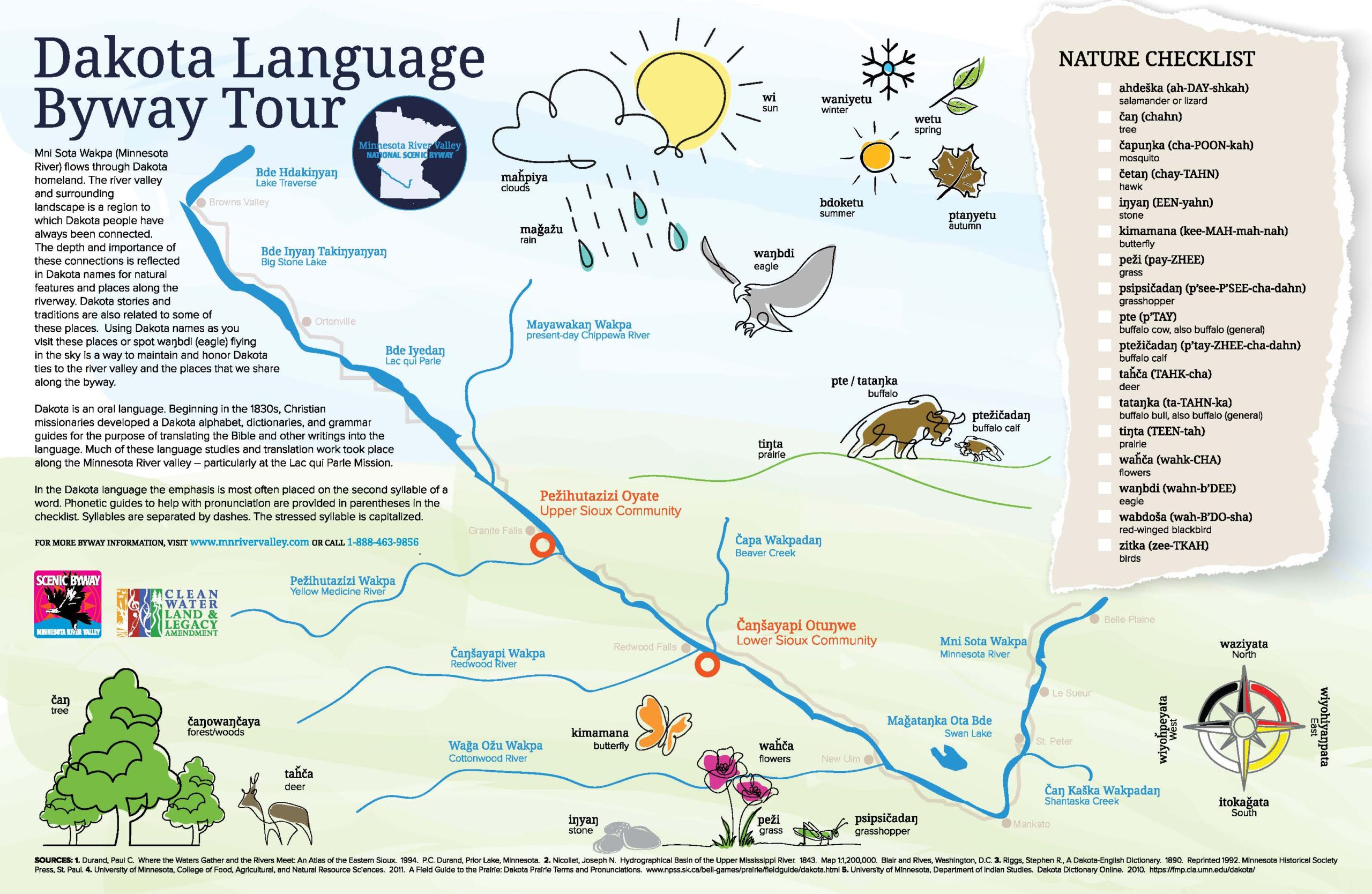

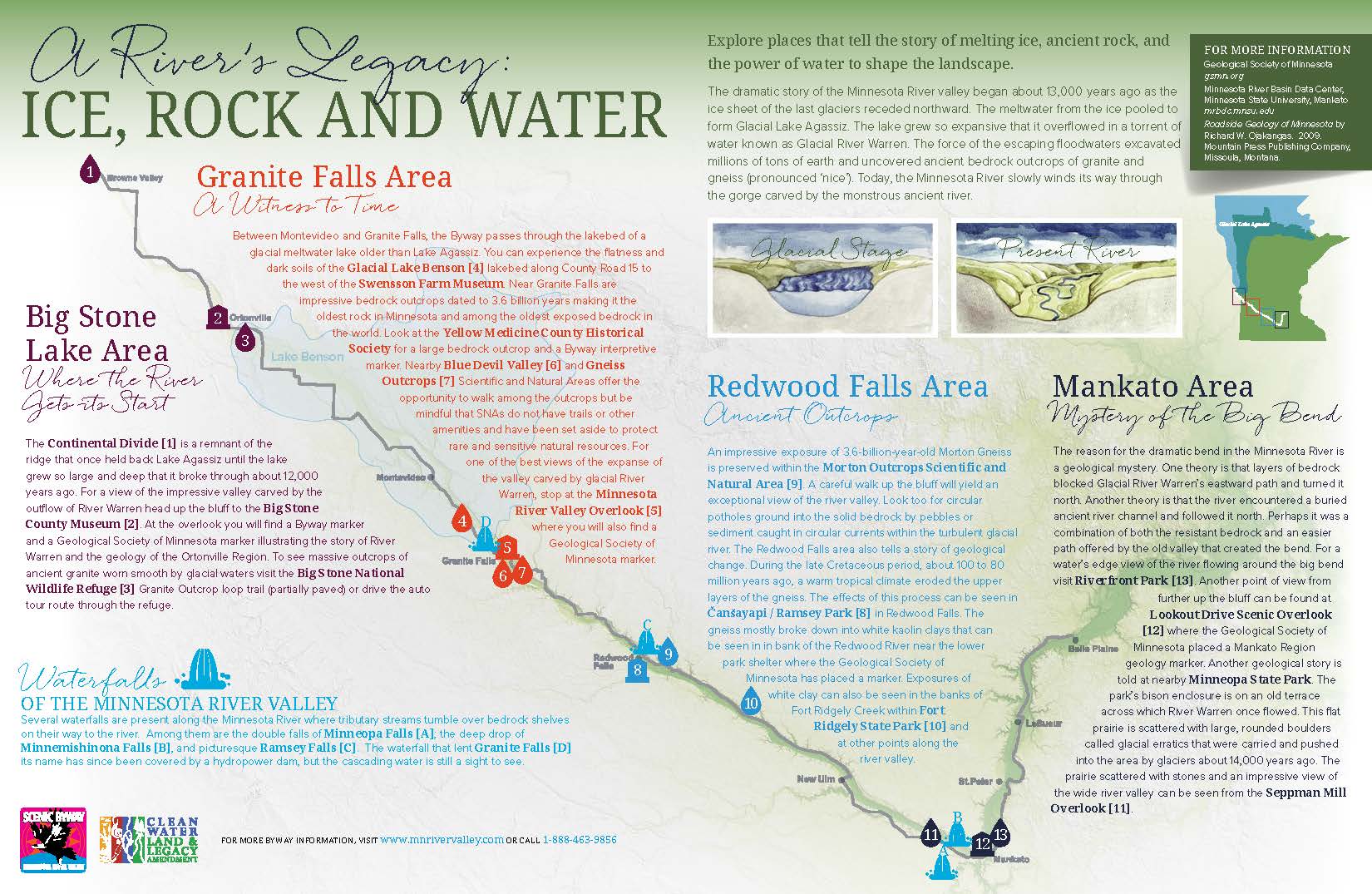

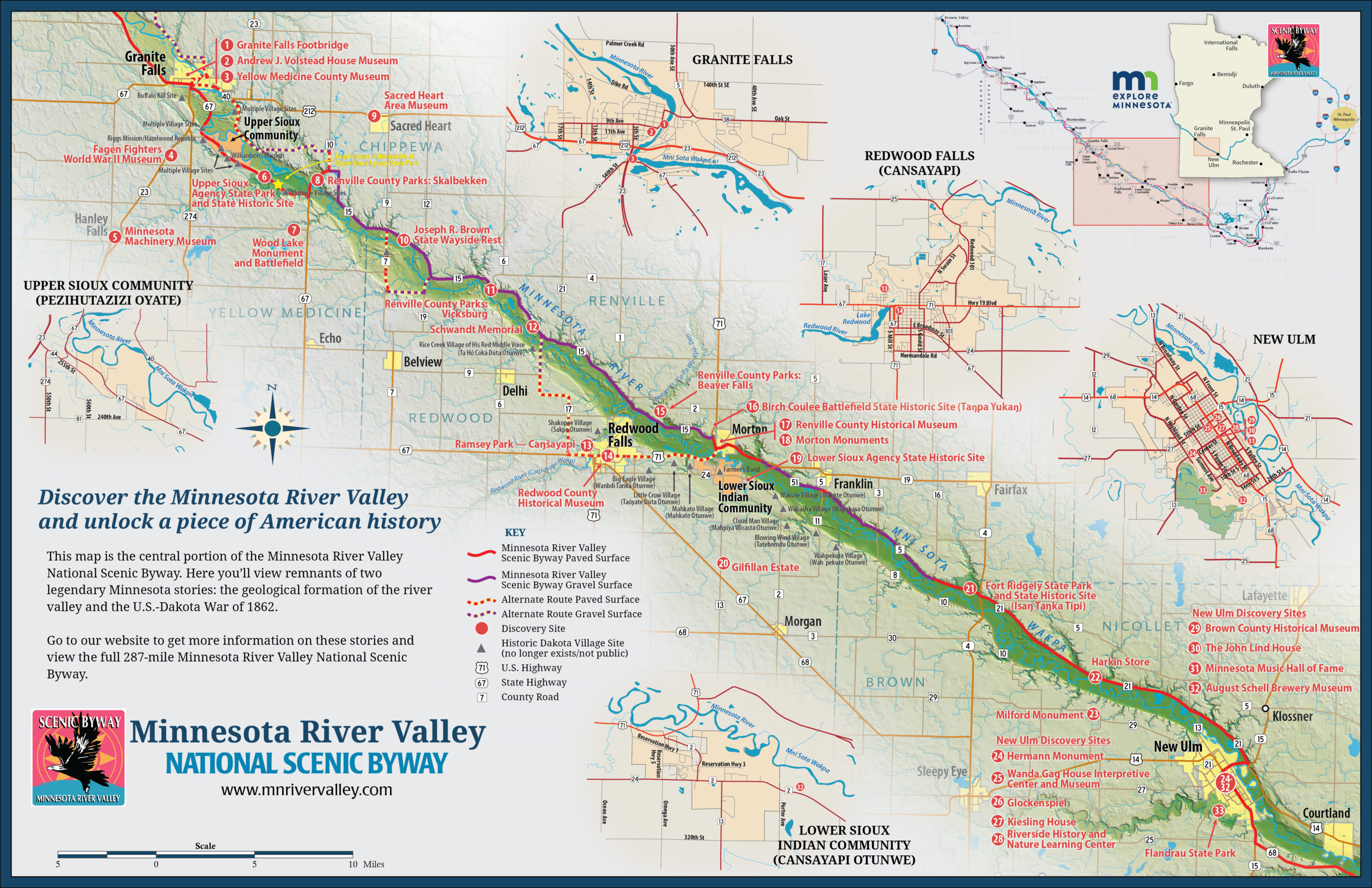

The byway has three new maps of the byway. These are great detailed maps that are mark our discovery sites and have more information on the back side.

Click below on a map for an orientation map. Also called a “Tear Map”.

These are 11×17 and printable.

West Map ♦ Central Map ♦ East Map

West Map

Central Map

East Map